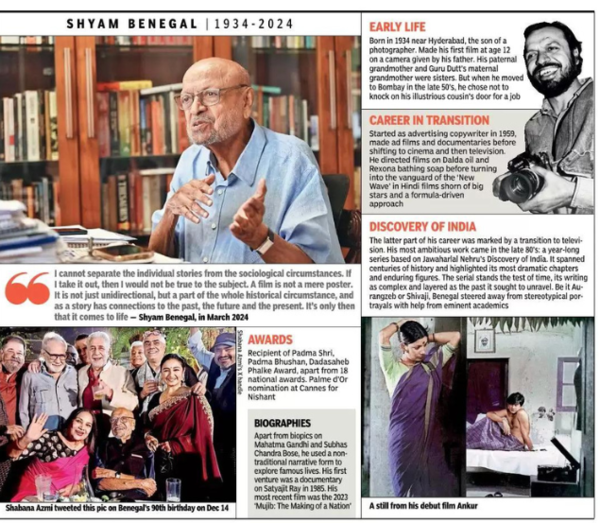

Shyam Benegal came out of nowhere and lit up the Hindi film scene in the 1970s at a time when the industry was “an absolutely closed shop”, as a close associate recalled it. It was the age of melodrama and action – ‘Roti Kapda Aur Makaan’ and ‘Sholay’ were big hits – and every release flaunted a roll-call of stars. “There was no possibility for any young filmmaker to get into it at all,” is how Girish Karnad, who was then director of the Film and Television Institute of India, described it.

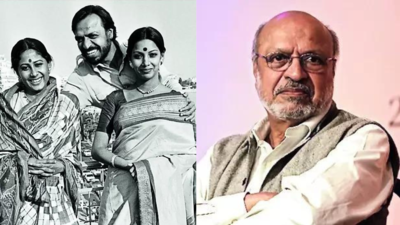

Benegal’s neorealism struck a deep chord with a generation keen on films that would mirror the social and political tensions of their time. His debut film ‘Ankur’ (The Seedling), a tale of sexual exploitation set against a feudal background with a cast of unknown yet riveting newcomers, ran 25 weeks at the landmark Eros theatre in Bombay. He had begun writing the script of ‘Ankur’ when he was in college in Hyderabad and spent 20 years looking for a financier before an ad film distributor agreed to produce it. Its success staked out new ground for the ‘art/parallel cinema’ movement that over time showcased new talent such as Naseeruddin Shah, Shabana Azmi, Smita Patil, Om Puri, Govind Nihalani, Vijay Tendulkar and Vanraj Bhatia.

Benegal, who pioneered parallel cinema in India and created the 53-episode Bharat Ek Khoj, and whose last project was a 2023 biopic on Mujibur Rahman – ‘Mujib: The Making Of A Nation’ – passed away in a hospital in Mumbai, days after he turned 90 on Dec 14.

Shyam Benegal grew up in a cantonment town near Hyderabad in 1930-40’s where his father, a professional still photographer, introduced him to the camera. The obsession with movies began early, his appetite whetted by Hollywood and Indian releases screened at a local hall for the morale of the troops. “There used to be two programme changes a week,” he once recalled. “…like in Cinema Paradiso, I befriended the projectionist so I could see both…”

Shifting base after his education, he began working at Lintas in Mumbai as a copywriter. The next decade and a half were spent on a prodigious number of ad films and documentaries. Traces of the social concerns underpinning his cinema are evident in the shorts he made, including the earliest ones, such as A Child of the Street, which took a compassionate look at juvenile vagrancy, and Close to Nature, a colourful take on tribal life in Madhya Pradesh.

His stint as a teacher at the Film and Television Institute of India (FTII) drew him closer to celluloid. But his bleak stories still had no takers among financiers. Lalit Bijlani of Blaze Advertising eventually stepped in. Both Ankur and Nishant, which came a year later, were set in the feudal lands of Telangana, a region under the Nizam. It was a world Benegal had seen up close in his formative years. Touted as his most striking works, the narratives and characters were situated in a rural milieu with a distinct dialect and attendant class-caste equations. Coming around the time of the Emergency, the two films spurred a movement of sorts and cemented his reputation as the high priest of the ‘New Wave’.

Benegal’s eclectic interests showed in the diversity of subjects. From Gujarat’s milk cooperatives (Manthan) to the life of a silent film era actress (Bhumika), from 1857 (Junoon) to feuding business families (Kalyug), his projects spanned periods and themes. A bearded, Renaissance figure at the centre of the ‘art film’ circuit, he was equally a mentor to actors, musicians, writers and technicians. At a felicitation to celebrate Benegal’s 25 years as a filmmaker, actor-playwright Girish Karnad spoke of his innate ability to help artistes tap their potential. “He was not just a director but also a doctor, a psychiatrist, a father figure and a banker,” said Karnad.

The latter part of Benegal’s career was marked by biopics, including one on Gandhi’s years in South Africa and a tetralogy on Muslim women (Mammo, Sardari Begum, Hari-Bhari and Zubeidaa). By then, the ‘art film’ movement had dissipated. He had turned to a new set of collaborators, many from commercial cinema. His standout work in this period, however, was a part elegiac, part quirky interpretation of a Dharamvir Bharti novel, Suraj Ka Saatvan Ghoda. Occasional forays into television too made for interesting viewing: Bharat Ek Khoj, the mega-series based on Jawaharlal Nehru’s Discovery of India, and Samvidhaan, on the making of the Indian Constitution, were the best examples.

Benegal’s influence on the Indian film industry extended far beyond his own body of work. He headed a govt committee set up in 2016 to streamline the film certification process and lay down a framework that would allow more room for artistic expression.